the danish testament

I’m working on an art project that deals with the idea of inheritance, legacy, and prophetic transmission. Sometimes we inherit things that are not intended for us. And yet we take them and transform them. We follow their red thread and they become part of our legacy. When we succeed in making a strong transmission inspired by what we receive by chance, we experience the tone of prophecy: ‘this shall be thy lot…’ A testament to the ominous, the wondrous, and the voracious in magic.

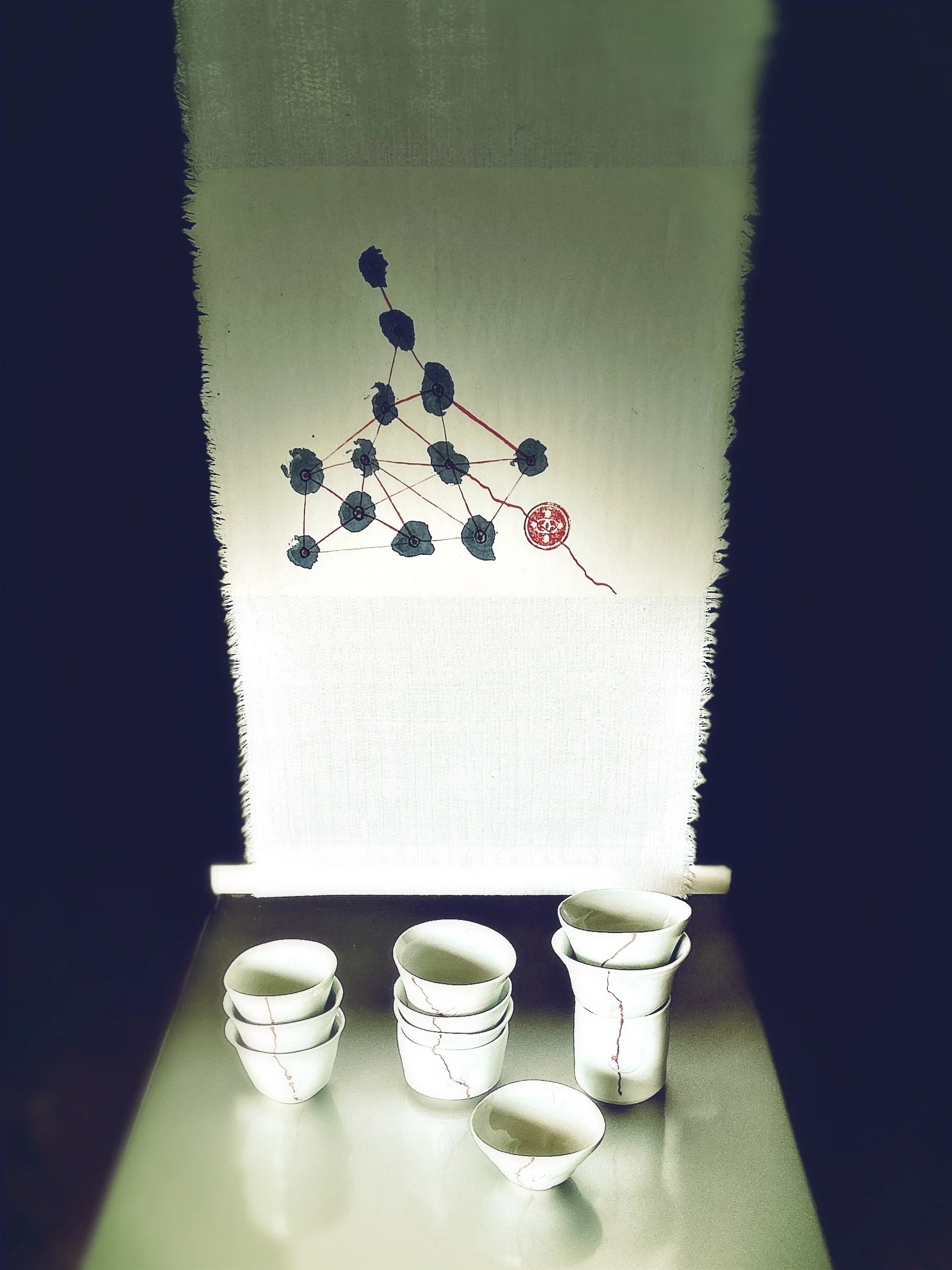

So far this project comes in two parts: one about making porcelain vessels and scrolls out of Danish vintage linen and damask table cloths, and another about making analog photographs. Each is accompanied by writing, either in the form of a book or a collection of essays.

PORCELAIN

It started with a stoneware ceramics bowl. I made one such when my sister gave me a birthday present in the form of a workshop in hand building. I had never touched clay before. After two hours of transforming it into a perfect bowl, I began to wonder about porcelain.

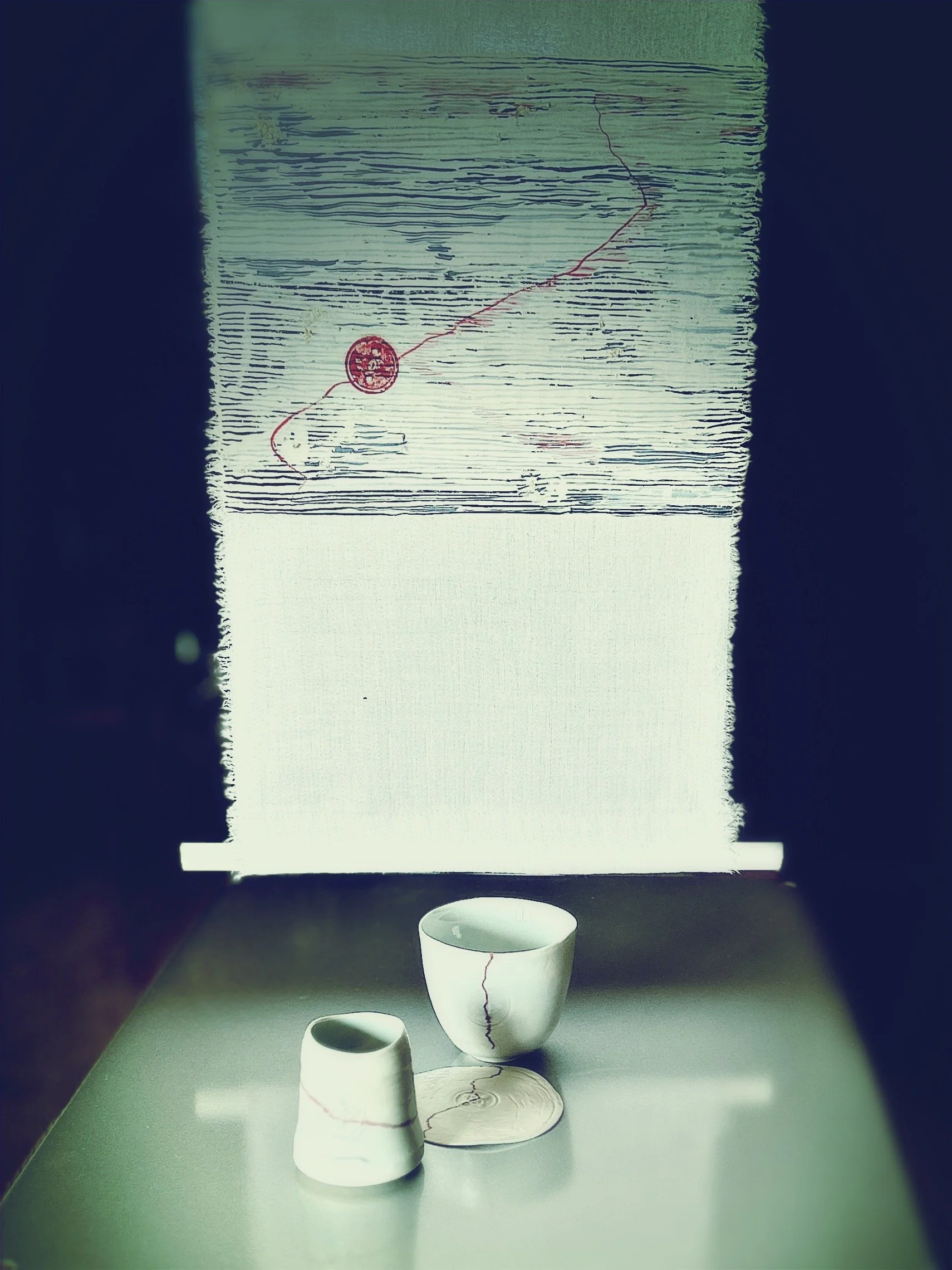

I had a an art project already in my head, one that involves linen, calligraphy, and translucent vessels: I make calligraphy scrolls out of Danish vintage linen and damask table cloths that I have been collecting for 35 years. Having discovered clay, it was a matter of minutes before I was ready to pair my linen scrolls with porcelain vessels of my own making and design.

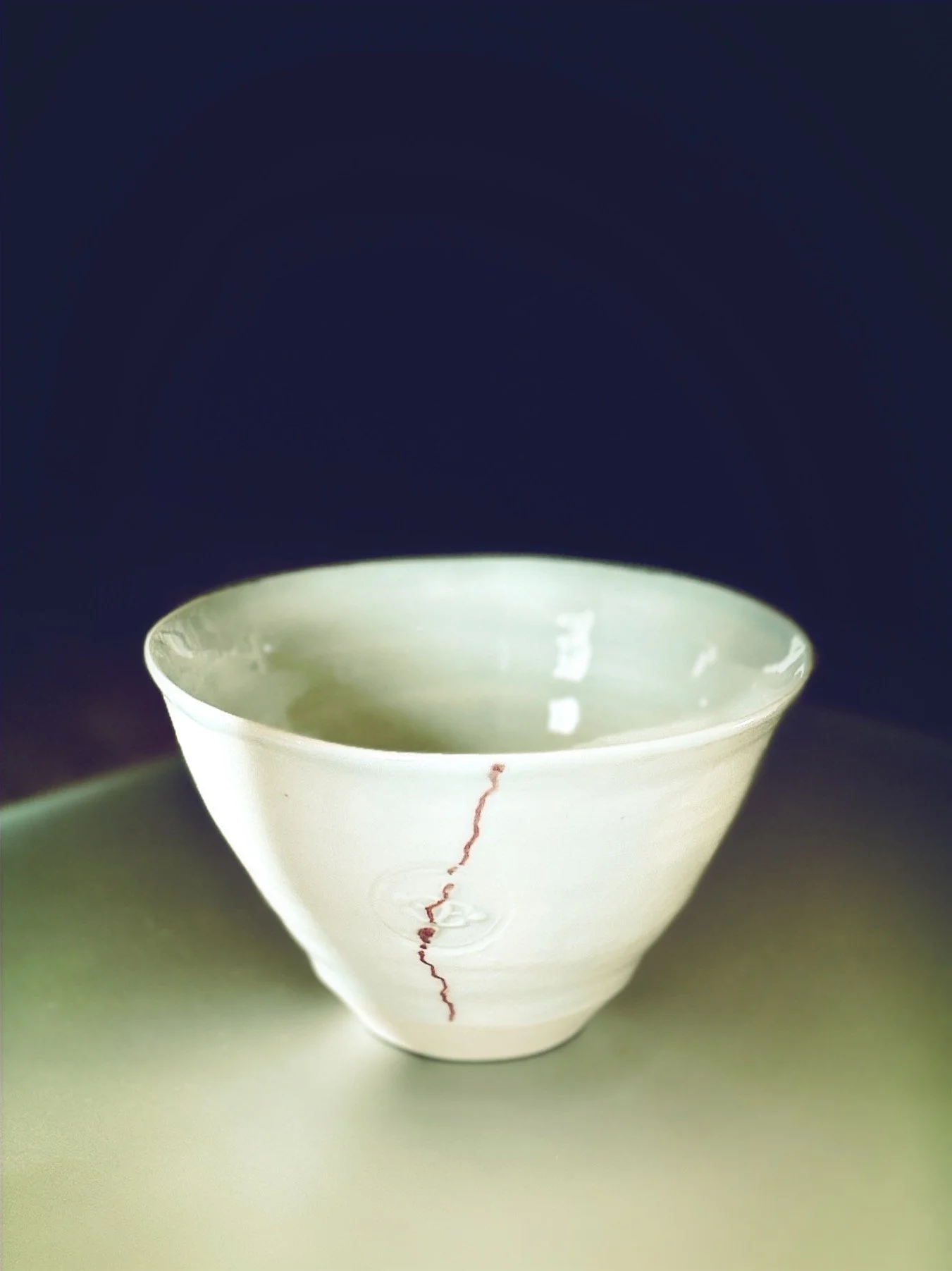

Decorated solely with my personal stamp for this project, my vessels are an expression of what I’m pursuing: holding the key to the essential. My interlaced initials, ‘ce’ accompanied by tulips, are an emblem of precisely this: clavis et essentia, revealing the energy that I infuse my work with in search of the keys to the impenetrable obvious.

I’m grateful to the curators of the Hans Bakggards Mindelegat for the culture grant they awarded me in support of this project.

Eat, feast, and read the writing on the wall

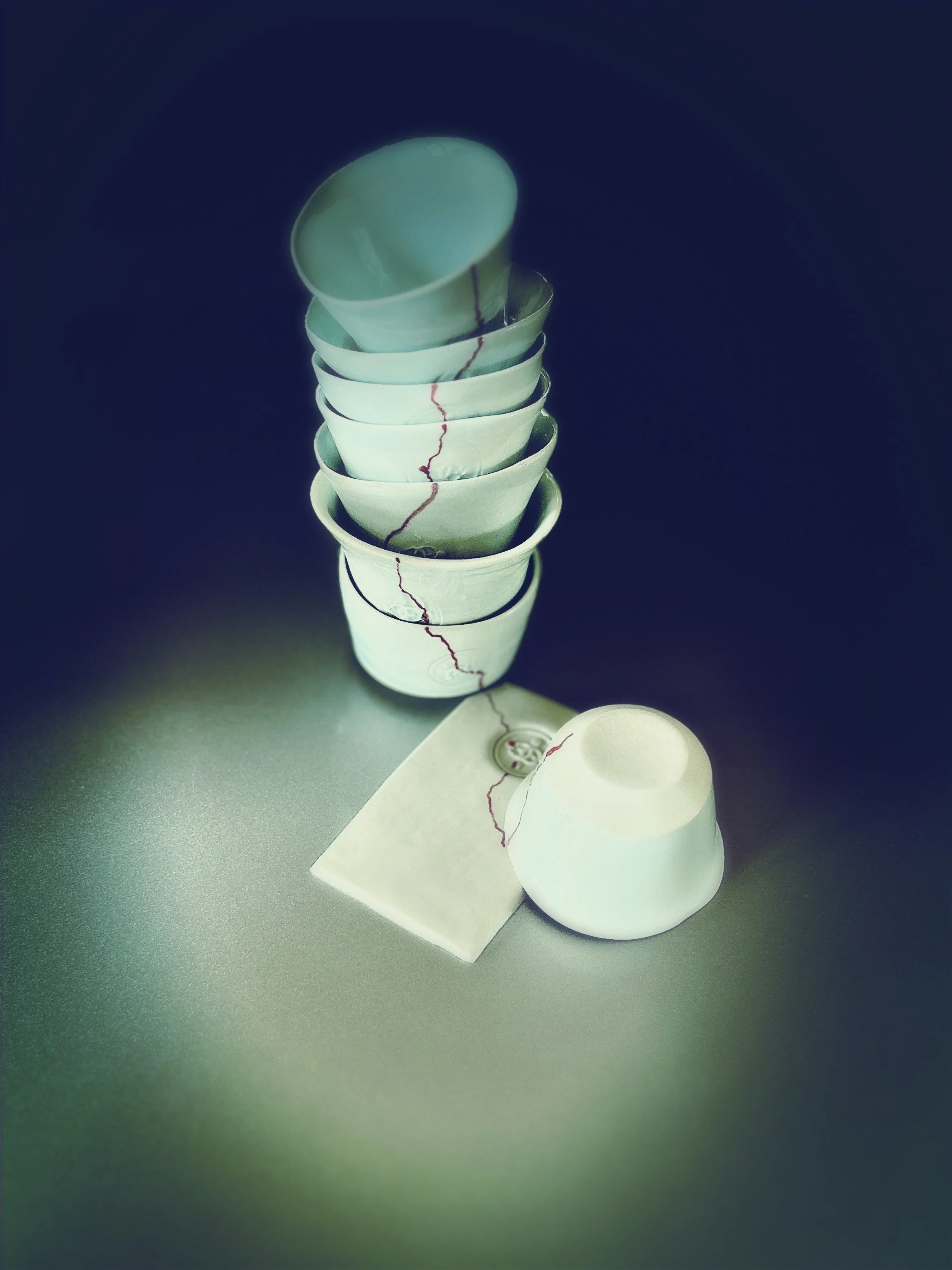

Although I’m in a frenzy about them, the idea is not to make pots as such – the world is full of pots and competent potters – but rather to think of how we can participate in voluntary and involuntary inheritances, adding to them our own testament in the form of fragments of memory that carries our own touch.

Once upon a time I wrote a big book on the history and poetics of the fragment. Twenty-five years down the road, I seem to return to the idea…

In this case here, I hold the key to an ingenious secret about how to mount a scroll that is in perfect affinity with porcelain work, an idea that came to me as I was pondering the concept of the fragment.

Currently I’m preparing an installation that juxtaposes my scrolls with my porcelain vessels. Imagine eating and seeing the writing on the wall. In Biblical times that was ominous. As I read the book of Daniel, I think of Belshazzar’s feast and the hand that appeared out of nowhere to write indecipherable words on the wall that only the prophet Daniel could interpret. The message foretold the division of the Neo-Babylonian kingdom.

In my art project I’m interested in the prophetic transmission that hits us in the gut, like a testament of sorts that obliges us to think of acts of giving and receiving that go beyond the mere rational.

Below is an example of what I make of the red thread in my transmissions and how I think it participates in the stacking of my narratives and storytelling. It begins with the Danish brides receiving the finest linen table cloths as part of their dowry, now passed on to me by chance…

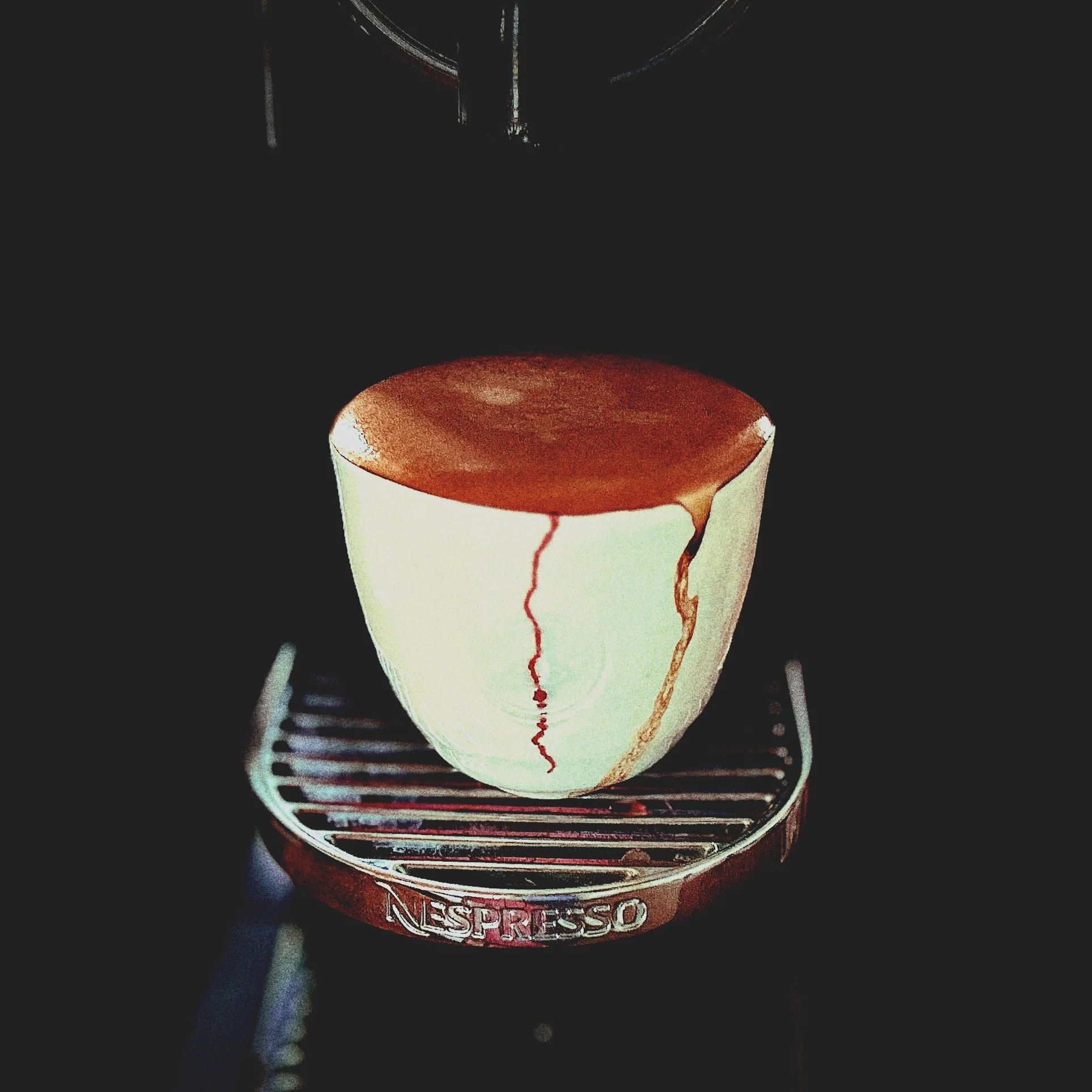

The vessels in this collection are all handmade on the wheel, calligraphed in red clay, and celadon glazed.

Below, my first attempt at doing anything ceramics. Although my focus is mainly porcelain now, I also like to use other types of clay that are porcellanous, as they have a resonance all their own. The first images here represent a few examples of my hand at work in the same week when I gave shape to clay without the help of wheels, moulds, or other forms: a conic bowl, my first, then perfume bottles, a tumbler, and a pitcher that gives spectacular control over pouring. Then porcelain and an attempt at making raku. Porcelain wins.

analog photography

After 40 years of a break, I returned to the magic of darkroom photography in order to put together a series of gelatin silver prints. As I inherited a Leica M2 from 1963, I wanted to honor its previous owner, historian and collector K. Frank Jensen. Part of this project has been turned into a book of fragments and photographs, Being Besides Myself.

The special edition book that was offered as a talisman came with a gelatin silver print. While this edition, book + silver print, is sold out, the hardback is still available.

a touch of silver

After 40 years of a break, I returned to the magic of darkroom photography in order to put together a series of gelatin silver prints. As I inherited a Leica M2 from 1963, I wanted to honor its previous owner, historian and collector K. Frank Jensen. Part of this project has been turned into a book of fragments and photographs, Being Besides Myself. The special edition book that was offered as a talisman came with a gelatin silver print. While this edition, book + silver print, is sold out, the hardback is still available. But what are we talking about when we say, analog photography? Let me introduce you to it.

Gelatin silver or silver gelatin? Which comes first? Technically speaking, hand printing on baryta paper, or fiber-based paper of hefty weight, refers to an embedded process: shooting black and white film, developing it, and printing it in the darkroom. The latter process involves enlarging the negative, and burning the baryta with light. The paper is then tossed into three chemical baths. What follows is washing, toning and drying. Now you know why a gelatin silver print can fetch half a million dollars – if you’re Robert Mapplethorpe.

THE TECH

The baryta paper contains a suspension of the silver halides, or salts in a gelatin layer. An image printed in the darkroom ‘sits’ on four layers: Cotton-based paper, baryta, gelatin binder, and a protective gelatin overcoat. As the silver is suspended in gelatin, we’re talking about a gelatin silver process, though many prefer the denomination, ‘silver gelatin,’ as it sounds better.

After enlargement, focus, and contrast control, the paper travels to three trays of wet dipping containing chemicals: Developer (I like the Romanian word for it, revelator, or revealer, as that’s what this chemical does, reveal the hitherto embedded but hidden image on the paper), a stop bath, preventing the paper from further developing, and a fixer ensuring that the paper will not be sensitive to the light anymore.

Afterwards the baryta requires a long bath in running water, typically an hour. This ensures that the added chemicals in the paper are washed out completely, so no staining can occur at a later stage.

Toning the baryta in selenium adds longevity to the print, and a dash of heightened contrast. Sepia toning or a similar chemical treatment can give the gelatin silver print a preferred look, while also making sure that your work will last at least 100 years without any change: the black stays black, and the white stays white (or tobacco and blue color, if toning was used).

I like my own prints to display fat contrast. Not necessarily grainy or sharp, but fat.

My second print that I processed after returning to the darkroom — when all darkroom experience, only one-week 40 years ago, completely vanished — was based on a thin negative. This means that it took the light from the enlarger a very short time to burn the hell out of the paper, thus leaving behind a layer of black that’s hard to describe.

All I can think of is the fat color that the Renaissance masters used when they painted their chairoscuro masterpieces. I tried to take pictures of this print below, The Hand and the Hound, and found it impossible to render without a perfect reflection of my iPhone in it. The surface is like obsidian, filled with strange depth and magic.

WRITTEN ON THE BODY

The point of this post about the basic process is to say the following:

Anything that requires your hand touch, even when the hand must be begloved, is magic. I take the saying, ‘keep it close to nature’ to my heart. There are minerals and chemicals that go into your hand touch. Your body is made of minerals and chemicals. So what you work with is actually the memory of your body. A miracle.

It may well be that the name ‘photograph’ means ‘writing with light’, but I like the idea that this writing with light is all about memory written on the body.

If you craft anything with your hands, keep going. There’s nothing like going through a process that requires your touch. That’s where the art of it is. In the touch.

When the touch of the baryta is the result of being utterly relaxed and utterly concentrated at the same time, you end up with work that not only touches the heart, but grabs it too.

And that’s the point of art: to grab the heart in a unique way and as a singular expression. After all, according to Zen masters, you’re all you’ve got. There are no others. The space you think you inhabit is not one that defines you, but rather, one that you create. On point, and with everything else that is in it.

I go out with my inherited Leica M2, the subject of The Danish Testament, and don’t look at things. I look at blobs of light and the horizon of our crossing of aims. I consider the notion of contrived pictures and try to situate myself in accordance.

I say to the light: ‘I see you light, I’m going to touch you.’ I can hear the silver halides getting all bubbly inside, waiting for my touch.

♦

being besides myself

In addition to being sold to others on commission or as part of occasional offers, some of my gelatin silver prints made it in a book of fragments, Being Besides Myself, where I look at photography as a talismanic object.

The book is available from EyeCorner Press in two further editions: hardback and ebook.

For more words on photography, see my essay, Contrived Pictures.